Karolinska Institutet and the History of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

31 May 2011 (revised May 20th, 2016)

Jan Lindsten

KAROLINSKA INSTITUTET was founded in 1810 with the aim of educating physicians and undertaking medical research. At the start, the staff comprised only six professors, each of whom had one research assistant. Today (2014) the institute is a prominent international medical university that offers 37 educational programs, has 367 professors in residence, and has managed and continues to fulfill its mission to improve health in the population by research, education and information.

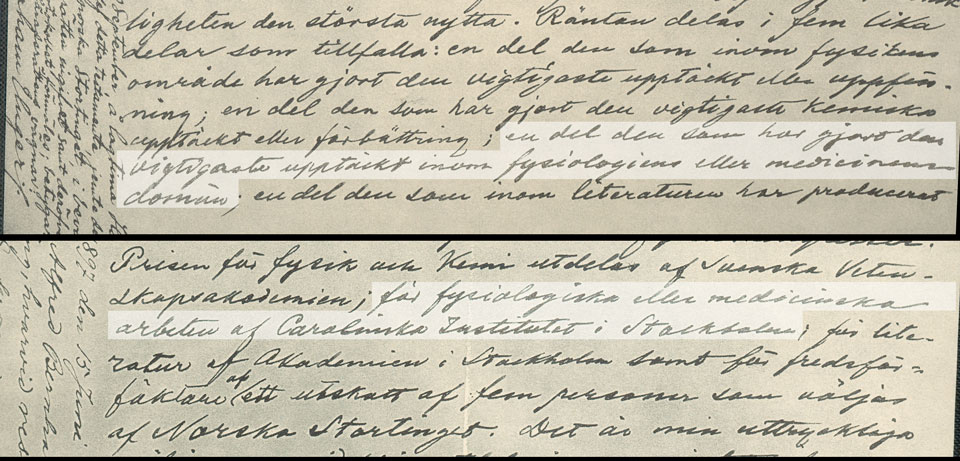

One of the most important events in the history of the institute was the commission by Alfred Nobel (Fig.1) to select Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine (Fig. 2).

Fig.1. Bronze bust (102.3 cm high) of Alfred Nobel engraved by Erik Lindberg (1873-1966) in 1910 and cast by Herman Bergman Fud. Foundry in Stockholm. It was donated to Karolinska Institutet by Alfred Nobel’s nephew Emanuel Nobel (1859-1932). He was a Swedish-Russian oil baron and the eldest son of Alfred’s brother Ludvig Nobel. The bust was raised in the courtyard of Karolinska Institutet at Kungsholmen in 1912. It was transferred to Karolinska Institutet´s present campus area in Solna, most likely in 1947, and placed (strangely enough not firmly fixed to the base which nowadays would be unthinkable) in between the buildings housing the three sections of the Medical Nobel Institute. In 1993 it was transferred again, but only 100 m, now to the entrance of Nobel Forum. Today, it is place inside Nobel Forum in Solna. The bust has been cast in several copies, but exactly how many is not known since the foundry, although still in business, has not kept a register of its products. We know of three additional copies; one is owned by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, one by Nationalmuseum in Stockholm (who bought it at an auction in 2009 and exhibits it in the National Portrait Gallery at Gripsholm Castle), and one by the Norwegian Nobel Committee in Oslo. Photo: Jan Lindsten

Fig. 2. Detail of part of Alfred Nobel´s will dated 27 November 1895. The section reads as follows, translated into English: ….. , the interest on which shall be annually distributed in the form of prizes to those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit on mankind. ….. The said interest shall be divided into five equal parts, which shall be appointed as follows: …..; one part to the person who shall have made the most important discovery within the domain of physiology or medicine;….. The prizes ….. that for physiological or medical works by the Caroline Institute in Stockholm; ….. .

Following the death of Nobel on 10 December 1896, the general idea of the Nobel prizes was not immediately embraced. It was only after several years (1897-1900) of lengthy discussions and the establishment of statutes for the Nobel Foundation, as well as for the prize awarding institutions, that the first Nobel Prizes were awarded in 1901 (see www.nobelprize.org). Few, if any, assignments have had a greater impact on the development of Karolinska Institutet than this task. It has not been possible to elucidate exactly why Alfred Nobel selected Karolinska Institutet as a prize awarding institution, but the following contributing factors have been mentioned: he was born in Stockholm; when his mother died he donated a fund to the institute in her memory (30 December 1890); and, perhaps most important of all, in his capacity of a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, he was very well informed about Swedish academic life during the second half of the 19th century. He may also have been influenced by a young researcher from the institute, Jöns Johansson (later Professor of Physiology and Chairman of the Medical Nobel Committee at Karolinska Institutet), who spent part of the years 1890-1891 working with blood transfusion experiments in Nobel´s laboratory in Sévran outside Paris. It seems that Nobel discussed matters related to his future will with Johansson, and that these discussions may have been of importance for how the will was drawn up. (Nobel made some notable changes to an earlier version of the will, dated 1893, which can be seen in the final version).

Guidelines for the Nobel Work

The Nobel work at Karolinska Institutet still follows the ideas and rules laid out in Alfred Nobel’s will, which were specified in greater detail in the statutes. Some of the rules require additional comments.

The prize is given for works within the field of Physiology or Medicine, not Medicine alone. Since Physiology in the days of Alfred Nobel implied the preclinical medical sciences and Medicine the clinical sciences this makes it possible to consider work within the entire field of experimental medicine, as well as research aimed at curing human diseases. This makes it possible to select prize laureates from all areas of the biomedical field, including related behavioral sciences, such as was the case when Karl von Frisch, Konrad Lorenz and Nikolaas Tinbergen received the Nobel Prize in 1973 for their discoveries concerning organization and elicitation of individual and social behavior patterns.

Alfred Nobel had been very interested in physiology as well as in medicine in general, as can be judged from his private book collection. This may have influenced his choice of Physiology or Medicine as a prize field. In fact, it has been claimed but not verified that he had originally intended to provide for only one prize – in Medicine. However, an internationally recognized academic scandal at Karolinska Institutet made him change his mind. (The scandal had to do with the very first appointment of a Professor of Ophthalmology in Sweden.) In the end, Nobel listed five Nobel Prizes: Physics, Chemistry, Physiology or Medicine, Literature and Peace.

The key words in the will are discovery and greatest benefit for mankind. This means that prizes are not awarded for illustrious scientific careers, however long and rewarding, but for specific discoveries. And benefitting mankind can include anything from increasing our basic knowledge within a particular subject to actually saving people’s lives. The wording might seem loosely defined, but it has turned out to work satisfactorily, and it forces the Nobel Assembly in Physiology or Medicine to constantly review how the meaning of the will should be interpreted in light of developments within the biomedical field.

The prize can be given to one, two or three laureates each year, none of whom should be an organization. When three laureates are awarded the prize, a procedure that has become more common with time, it is up to the Nobel Assembly to decide how to divide the prize money between the laureates (one third each or half to one with the other two sharing the other half). The question has been raised whether or not awarding just a maximum of three laureates annually is enough, considering that the international scientific community has grown considerably since 1901. However, so far this hasn’t proved to be a problem since a discovery cannot be deemed entirely unique if more than three scientists have contributed. Normally a prize can not be awarded posthumously.

Altogether 193 laureates have received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine from 1901 to 2010. Five of these worked at Karolinska Institutet (Hugo Theorell 1955, Ragnar Granit 1967, Ulf von Euler 1970, and Sune Bergström together with Bengt Samuelsson 1982). Detailed presentations of all nominated candidates and Laureates are found on nobelprize.org LINK TO PAGE. A description of the evaluation process behind the prize can be read under “SELECTING LAUREATES/An overview” LINK TO PAGE.

The will states that rewarded contributions should have been achieved during the preceding year. This, however, has only rarely been possible to manage. Even if a discovery is considered to be of great potential importance at the time of its publication, it always takes a while before it has been definitely confirmed. Further, should it ever be the case that the importance of a discovery indeed is apparent already in the following year, there can be so many worthy candidates that the evaluation process becomes delayed.

All prizes, especially prestigious ones, are subject to criticism, and the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is not exempt from this. The criticism has mainly been concerned with either omissions or mistakes. Omissions have been made, but they are undoubtedly bound to happen since the number of laureates is limited in relation to the number of candidates worthy of the prize, not least in today’s expanding scientific community. And of course there have been mistakes, bearing in mind that values vary between individuals as well as over time. Scientific developments also tend to show how previous concepts were based on incorrect conclusions. This is unavoidable. However, this does not take away from the fact that the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is the most glorious award in the world. Several factors related to Alfred Nobel’s will and the history of the prize have contributed to this. One of these is that although prizes for scientific achievements were not uncommon during the latter part of the 19th century, the Nobel Prizes were awarded on an international level, which, at the time of their introduction, represented a new policy. Further, candidates are nominated from within the international scientific community, the laureates are selected by a country that has upheld its reputation for neutrality, the evaluation process is comprehensive, and the prize money is considerable. Most important of all, the choice of laureates has been highly respected by the international scientific community.

Method of Working

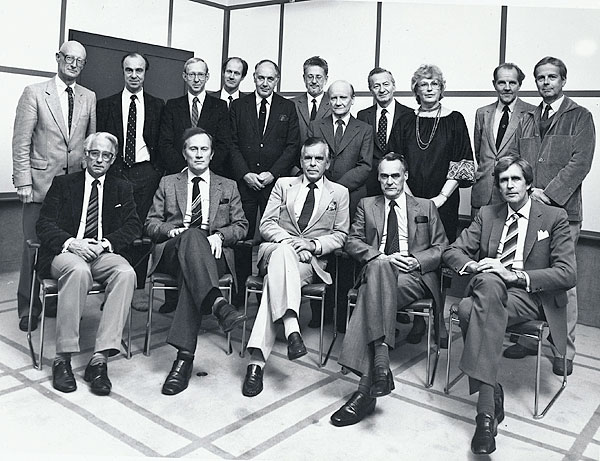

From 1901 to 1977, Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine were chosen by the senior teaching staff composed of all the professors at Karolinska Institutet. During the latter part of this period, the group was renamed the medical faculty. In 1910, it consisted of 22 people, and by 1960 the figure had grown to 45. Subsequently, the task has been taken over by the Nobel Assembly. The assembly works independently from the institute and consists of 50 professors from the institute (Fig.3). It is a self-perpetuating body, i.e. new member candidates are proposed

and elected by the existing members. The decision to change the organization in this way was made by the Swedish Government in 1977. The very first meeting of the Assembly occurred on 13 March 1978, and on 12 October the same year, it elected Nobel Laureates for the first time. The two main reasons for the change were (i) the introduction of a new Official Secrets Act by which all Nobel documents handled at the institute would become public, and (ii) a new and wider definition of university teachers was introduced, which would more than double the teaching staff at Karolinska Institutet.

When founded, the Nobel Assembly was composed of all members of the teaching staff, which numbered more than 50 people. This number was reduced by time when members retired. The first new elected member didn’t take up the position until 1984. Although the final decisions on Nobel Prize recipients are taken by the Nobel Assembly, all the preparatory work is undertaken by the Medical Nobel Committee (Fig.4).

The committee has five members (who serve a maximum term of office of two times three years). One of the members is also elected chairman for a maximum of three years. The committee members are all members of the Nobel Assembly. In addition, 10 ad hoc members are elected for a one year term of office. The ad hoc members contribute with specialized skills depending on the fields in which nominated prize candidates work. Ad hoc members are usually, but not exclusively, members of the Nobel Assembly.

Finally, the Assembly and the committee are served by a Secretary General (a member of the Assembly) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. (from left to right, top to bottom) Secretary-Generals of the Medical Nobel Committee since 1918, Göran Liljestrand, Ulf von Euler, Bengt E. Gustafsson, Jan Lindsten, Alf Lindberg, Nils Ringertz, Hans Jörnvall and Göran K. Hansson.

This post has over the years been held by Göran Liljestrand (1918-1960), Ulf von Euler (1961-1965), Bengt E. Gustafsson (1966-1978), Jan Lindsten (1979-1990), Alf Lindberg (1991-1992), Nils Ringertz (1993-1999), Hans Jörnvall (2000-2008), Göran K. Hansson (2009-2014) and Urban Lendahl (2015-2016). Currently, Thomas Perlmann (2016- ) is at the helm. As astute observers will have noticed, the committee did not have a Secretary General during the years 1901-1917, and the professor appointed as the first such secretary, Göran Liljestrand (Fig.6), held the post for no less than 42 years.

The rules were later changed so that the maximum term of office for the Secretary General became four times three years. Liljestrand (1960) famously described the secretarial work before his election in the following way:

The Principal actually worked out many of the medical faculty’s reports himself, and since he had also, ever since the establishment of the Medical Nobel Committee (1901), chaired the committee’s work and in this capacity managed the secretarial work, keeping all the committee’s minutes and handling all its outgoing communication, even writing all the addresses to the faculty members by hand and sealing them with wax, one realizes that there was little time left for undertaking own research, even if he did avail himself of his right to refrain from lecture duties.

Today, it can be said that the current organization of the Nobel work strikes a fair balance between continuity and renewal of the Committee as well as of the Assembly. However, one might ask whether the scientific competence available at Karolinska Institutet will be sufficient enough to cover the Nobel Assembly’s need for the expertise required to select Nobel Laureates in the future. Fortunately, the organizational structure and procedures summarized above, which include the possibility to engage international experts, appear to suffice in this respect.

Premises

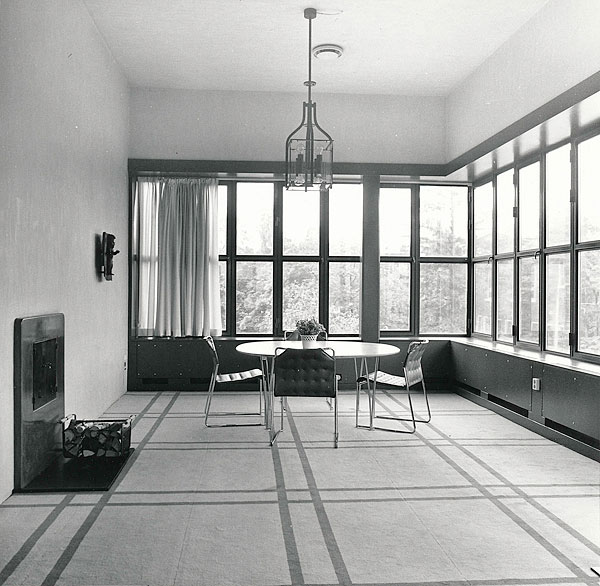

Up to the 1970s, there were no special premises for the Nobel activities at Karolinska Institutet. Meetings were held in conference rooms at the institute (Figs 7 and 8) and all the documentation was stored in the office of the Secretary General.

In the middle of the 1940s, the preclinical departments at the institute moved from the center of Stockholm, where they had been located close to the City Hall on Kungsholmen, to the present campus area in Solna. In 1946, the decisions regarding Nobel Laureates were for the first time taken in the meeting room of the medical faculty (Figs 9A and B).

Later, in the middle of the 1970s, the Secretary General was assigned a special office in an old wooden building on the campus (Fig. 10), where all documents could be locked in safety boxes.

Fig.9A The building in which the medical faculty met during 1946-1993 (Bottom floor to the right). Photo: Veijo Mehtonen

Fig. 9B. The meeting room in which the medical faculty met during 1946-1993.

Fig. 10. The barn at Karolinska Institutet’s campus area in Solna where the Secretary General had his office in the beginning of the 1970s. Photo: Mattias Karlén

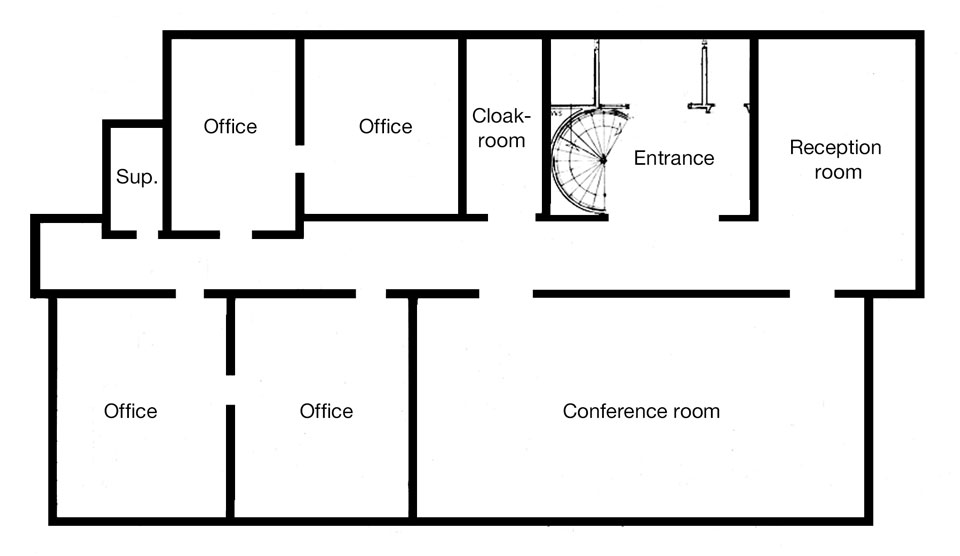

Fig. 11A. Architect Peter Celsing’s addition to the original administration building The Nobel premises were located on the top floor

Fig. 11B. Floor plan of the Nobel premises in the old administration building

Fig. 13. The exterior of Nobel Forum. The fountain to the right – Källan (The Well) – was made in 1997 by the sculptor Liss Eriksson and donated to Karolinska Institutet by Professor Sune Bergström. Photo: Mattias Karlén

Fig. 14. Nobel Lecture held by John Sulston in 2002, in Berzelius auditorium at the Karolinska Institute (Photographer not known)

A major change occurred in 1976 when the Nobel Committee got its own, new premises (Figs 11A-C, 12A-D) designed by the architect Peter Celsing. But even these premises turned out to be insufficient when the Nobel workload continued to escalate and the Nobel Assembly was founded. New premises had to be constructed to cover the needs of both the Assembly and the Committee. This is how Nobel Forum came to be built (Fig. 13).

It was designed by the architect Johan Celsing, son of Peter Celsing, and the construction costs were covered by donations to Karolinska Institutet from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation and the Nobel Foundation. Today, all meetings of the Nobel Assembly and Committee take place here, as does the official annual announcement of who has received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. However, not even these premises are large enough to encompass all those who want to listen to the lectures which the Nobel Laureates each year give according to the statutes (Fig. 14).

Although the largest lecture hall at Karolinska Institutet is used for these lectures, there are a great number of spectators who have to follow the lectures from outside the hall via closed circuit TV. The construction of a new large auditorium at Karolinska Institutet (Aula Medica) was inaugurated in 2013 seating 1 000 people, promising to be an excellent venue for future Nobel lectures.

The Medical Nobel Institute

The original statutes of the Nobel Foundation opened up for the possibility to create Nobel Institutes, as can be read in §11:For assistance with the scrutiny necessary for the prize adjudication and for the promotion in other ways of the purposes of the Foundation, the prize awarding bodies shall be empowered to set up scientific institutions and other establishments. These institutions and establishments belonging to the Foundation shall be called “Nobel Institutes”.

The issue of a Medical Nobel Institute was discussed repeatedly over the years, and in 1912, the well-known Swedish architect Ferdinand Boberg produced a drawing showing what such an institute could look like. However, it was not until 1936 that the decision to construct a Medical Nobel Institute was taken. The first head of this institute was Professor Hugo Theorell (Nobel Laureate in 1955), who in this way became committed to Karolinska Institutet as Professor of Biochemistry. Two additional sections within the Medical Nobel Institute were founded in 1945 – the sections of Neurophysiology headed by Professor Ragnar Granit (Nobel Laureate in 1967), and Cell Research and Genetics headed by Professor Torbjörn Caspersson.

The Medical Nobel Institute was partly financed by the Nobel Foundation until 1972, when full financial responsibility was taken over by the state, i.e. Karolinska Institutet.

After the retirement of the original directors, the Medical Nobel Institute gradually changed character and its sections became integrated into the academic departments of Medical and Physiological Chemistry, Neuroscience, and Cell and Molecular Biology at Karolinska Institutet. Funding for research had been taken over by Karolinska Institutet and external funding agencies such as the Swedish Research Council. As a consequence, and in line with similar developments within the Nobel Institutes for Physics and Chemistry, the Medical Nobel Institute was reorganized in 2010. It now handles the external academic activities of the Nobel Assembly, including its series of Nobel Conferences, Minisymposia, Research Lectures, and Nobel Laureate Revisiting Lectures. It is led by the Secretary General and has a Governing Board with representation from the Nobel Committee and Karolinska Institutet.

Conferences and Lectures at Nobel Forum

The Nobel Assembly sponsors several important conference and lecture series held at the Nobel Forum. They include Nobel Conferences, which deal with important themes in life science or medicine and usually last two to three days, and Nobel Minisymposia, which are one-day conferences addressing more focused topics. Scientists at Karolinska Institutet are usually in charge of each conference, with the administrative and financial work handled by the Medical Nobel Institute. A list of all previous Nobel Conferences and Minisymposia is found HERE. Planned Nobel Conferences and Minisymposia are announced regularly on the front page.

In 1993, a lecture series was initiated by the Nobel Assembly together with Karolinska Institutet. Leading scientists around the world are invited to present their research in this series, which is called the Karolinska Research Lectures at Nobel Forum. These lectures are announced throughout the Institute, and the audience consists of Nobel Committee members, professors, postdocs and students. Around six to seven lectures are held every year.

By far the most prestigious lecture series is the one held by the Nobel Laureates. As stipulated in the bylaws of the Nobel Foundation, each Nobel Laureate shall give a lecture on formally receiving the Nobel Prize. Laureates in Physiology or Medicine give their Nobel Lectures at Karolinska Institutet, usually on the 7th or 8th of December each year.

Former Nobel Laureates frequently visit Karolinska Institutet and the Nobel Assembly. In addition to consultations with the Nobel Committee and with Karolinska faculty members, they are invited to give lectures in a series entitled Nobel Laureate Revisiting Lectures. This is a much appreciated opportunity for an update on research performed by Nobel Laureates after they received the Nobel Prize, since many laureates continue to be highly active.

Sources

Crawford, Elisabeth. The Beginning of the Nobel Institution. The Science Prizes, 1901-1915. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge-London-New York-New Rochelle-Melbourne-Sydeny, 1984.

Lennmalm, F. Karolinska Mediko-Kirurgiska Institutets Uppkomst och Utveckling. Isaac Marcus’ Boktryckeri-Aktiebolag, Stockholm 1910.

Liljestrand, Göran. Karolinska Mediko-Kirurgiska Institutets Historia 1910-1960. Almqvist & Wiksell, Stockholm-Göteborg-Uppsala, 1910.

Ljungström, Olof. Ämnessprängarna. Karolinska Institutet och Rockefeller Foundation 1930-1945. Karolinska Institutet University Press, 2010.

Norrby, Erling. Nobel Prizes and Life Sciences. World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd., New Jersey-London-Singapore-Beijing-Shanghai-Hong Kong-Taipei-Chennai, 2010.

Schück, H, Sohlman, R, Österling, A, Liljestrand, G, Westgren, A, Siegbahn, M, Schou, A, Ståhle, N K. Nobel. The Man and his Prizes. Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam-London-New York, 1962.

Layout: Mattias Karlén